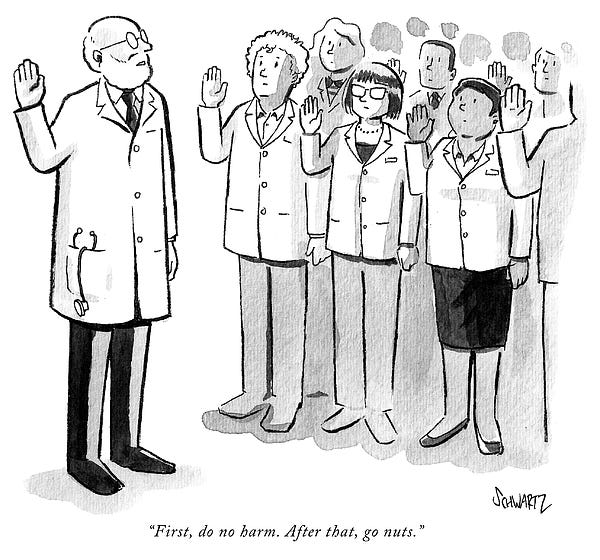

First, Do No Harm (After That, Go Nuts)

Time to dismiss the parenthetical and get back to first principles

Ancient wisdom unequivocally holds that the prevention of harm should take precedence over the pursuit of benefit.

This principle has stood the test of time because harm, once inflicted, can be irreversible, whereas potential benefits often remain uncertain and context-dependent. The principle is enshrined in the western canon’s Hippocratic Oath, “First, do no harm” and is also characteristic of traditional eastern thought. However the modern west has to some extent abandoned this core principle in every area, even in the medical field, where, although it still enjoys some fame in the popular consciousness, little more than lip service is paid in actual practice.

The principle can be applied to any area of life, but hits closest to home when applied to medicine, since the consequences are so immediate.,

We’ll highlight it’s applicability to animal research studies in particular, but this investigation should also help to illuminate how this same principle might be applied across the medical field and in other areas.

Although initially the concept seems simple enough, there are some nuances that crop up in animal studies specifically which help to better elucidate why it should be taken as a first principle. Similar nuances will undoubtedly appear upon examining other areas be they in medicine, social justice, the law, the economy, the nuclear family, spiritual progress, etc. From examining the particulars of many cases we may eventually become convinced that we’ve struck upon a foundational principle upon which we can establish any endeavor, be it tending a garden or raising children.

Without this principle it’s easy to become lost in a forest of seemingly right choices that nevertheless somehow end up leading you to destruction. It’s not impossible that in certain situations surgery may be the right choice despite introducing limited harm, but unless we begin from the stance that all harm must be avoided, we won’t ever see the possibility that very often surgery isn’t actually required, especially if we move our interventions further up the long chain of events that lead someone to the operating table. To the one holding the hammer, every problem is a nail, unless they’re guided by some higher principles that shine light on their circumstances and help guide their decisions.

Here we but reintroduce the familiar old idea in a new light so that you may choose to apply the same lens everywhere else.

Reliability of Animal Models in Identifying Harm

When an experiment reveals that a substance or intervention causes harm in animals, this should always raise a red flag, despite differences in human physiology. That’s because animals, particularly those in artificially controlled laboratory environments, lack the complex psychological, emotional, and intellectual stressors that all humans experience. These stressors—rooted in the human prefrontal cortex and HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis, which take events and assign stressful meanings to them—directly influence our immune function, metabolic responses, and overall health.

Animals, in contrast, exist in a more controlled physiological state. Their responses to toxins are often more straightforward since they do not suffer from the chronic stressors of human life, such as financial worries, social conflicts, or existential anxieties. While it is true that laboratory animals experience their own forms of stress, including confinement and handling, these stressors are stripped of meaning, more uniform and predictable than the multi-layered psychological burdens that affect human biology.

For instance, research on zebras has demonstrated that after surviving a lion attack, they can rapidly return to a state of healthful parasympathetic nervous system dominance, allowing them to recover from the psychological trauma immediately, and if physically injured heal very rapidly. In contrast, human beings—who remain psychologically trapped in stress even long after the initial trigger—may take exponentially longer to recover, or in some cases, may never fully return to a parasympathetic state. This chronic nervous system dysregulation has profound implications for healing and chronic disease pathogenesis. For more on this, one can refer to Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.

Therefore, when animal studies show that a substance is harmful, it is prudent to take such findings seriously. If an organism that is naturally more resilient than humans succumbs to toxicity, it is reasonable to infer that humans—who are physiologically and psychologically more vulnerable—may be at even greater risk.

A common argument against the reliability of animal models for detecting harm is the thalidomide case, where birth defects were not observed in initial animal studies but later emerged in humans. However, this was not a failure of the animal model itself but rather a failure of study duration and design. If researchers had extended the observation period, they would have identified the teratogenic effects before the drug reached the market. Unlike human patients, lab animals can be discarded and forgotten, meaning adverse effects in animals may go entirely unnoticed or unreported if the study period is too short. This reflects not an inherent flaw in animal testing but rather scientific haste driven by economic incentives.

Similarly, cases like acetaminophen toxicity in cats illustrate another aspect of the equation. Some substances are toxic to certain species but safe for others, which highlights species-specific metabolic differences rather than a failure of toxicity detection itself. In some instances, species like cats that are more susceptible in some physiological aspects may exhibit a certain toxicity earlier than humans, but this doesn’t mean it won’t affect us, it’s more likely to mean those same adverse effects in humans may simply remain undetected or dormant longer, and will only show up in longer term human trials, which are rarely done.

The Pitfalls of Relying on Animal Studies for Benefits

Conversely, when an animal study claims a particular intervention is beneficial, we must exercise far greater scrutiny than we do for studies showing harm, before generalizing it to humans. Again, unlike humans, animals live with far fewer psychological burdens. Their primary concern is survival—availability of food being the most crucial factor. When well-fed and kept in generally optimal environmental conditions, animals essentially exist in a state akin to an idealized human life, free from major stressors. But can we extrapolate their positive responses to human beings, who are rarely (if ever) in such a perfectly controlled state?

To put this into perspective, imagine a hypothetical human study where all external stressors are eliminated—financial concerns, social conflicts, existential worries. While ludicrously impossible in real life, this scenario still might not even approximate the controlled conditions under which laboratory animals exist, because, in human society, even those who appear to have material wealth or ideal circumstances are not exempt from biological stressors such as social pressures, cognitive burdens, and subconscious anxieties.

Thus, when animal studies show benefits, we must rigorously question whether those same effects would manifest in real-world human conditions. The absence of major external stressors in lab animals can artificially enhance the apparent benefits of an intervention, making them unreliable predictors for human health outcomes.

Case Study: Rimonabant – A Cautionary Tale

A striking example of the limitations of animal studies in proving efficacy is the case of rimonabant, an anti-obesity drug. This medication functioned by blocking endocannabinoid receptors, thereby reducing hunger, promoting fat loss, and delivering other seemingly beneficial metabolic effects. If the research had been confined solely to animal studies, the drug would have appeared overwhelmingly positive, as animals displayed substantial weight loss and metabolic improvements. However, when tested in humans, an entirely different reality emerged. Rimonabant was eventually withdrawn from the market due to severe neuropsychiatric side effects, including depression and an increased risk of suicide. This raises a critical question: How would we ever assess an animal’s mental health in a way that translates to human experiences? An animal cannot verbally or in any way reliably express feelings of despair, existential angst, or suicidal ideation.

Beyond psychology, there is an even deeper issue at play: species-specific receptor distributions. The human endocannabinoid system (ECS) differs from that of test animals, affecting how drugs interact with neurotransmitters and brain function. The failure of rimonabant was not simply an issue of animals lacking verbal expression of distress, or researchers not noticing behavioural signs of the same; rather, it highlights how species-dependent receptor variations can lead to misleading conclusions in preclinical research.

The Imperative for a Balanced, Critical Approach

Given these limitations, it is imperative to apply a discerning approach to animal studies. When an experiment reveals harm, we should treat the findings with serious concern because animals, being physiologically resilient, may actually underrepresent human susceptibility to toxicity. However, when studies claim benefits, serious skepticism is warranted, as animals exist in vastly different psychological and environmental contexts.

In the relentless pursuit of profit, this principle has been completely overturned in today’s inflation driven hyper-capitalist world. Pharmaceutical drugs and even everyday household and consumer chemicals remain largely untested for long-term safety. A conservative estimate suggests that 60–85% of chemicals in common products have not undergone adequate safety testing, particularly for chronic exposure and endocrine disruption. Over 99% have never been subjected to long-term human studies. Most rely only on basic acute toxicity data (such as LD50 tests) while lacking comprehensive research on carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, and endocrine-disrupting effects.

Those who analyze scientific research in industry and at home as discerning consumers must understand the fundamental differences between human and animal physiology, stress responses, and receptor distributions. Failing to do so leads to misinterpretations that can have significant real-world consequences, as seen in the case of rimonabant.

Animal studies remain a useful but imperfect tool, and their results must always be interpreted in context. The real issue is not whether animal models work, but whether we are using them appropriately, with due diligence in study design and a commitment to prioritizing harm prevention over speculative benefits.

Only by scrutinizing studies from multiple angles, embracing a "devil’s advocate" mindset, and recognizing the vast complexities of human biology can we make informed decisions about the safety and efficacy of medical interventions.

First do no harm needs to be taken seriously again, and fanciful claims of doing good for society at large or people in particular need to be viewed not only far more critically, but also more suspiciously. Only then can we be truly safe from terrible, unexpected consequences in the modern world, where we have the power to split atoms, rewrite genetics, and litter the world and our own bodies to a degree utterly inconceivable before this age. Seriously considering all possible harms and forbearing to do something deliciously appealing and lucrative because of a responsibility of care to ourselves and society at large is simply the adult thing to do and it’s past time time the adults took charge again from the spoiled adolescents leading us to our destruction.

And surely, an early principle of medicine is diagnosis. We still have no testing and no way of confirming what long covid is, yet we have pundits everywhere telling us how to treat everything from persistent spike protein, through blood nanotech, to EMF, before anyone has worked out what exactly is harming us.

https://curingcoviddiseases.substack.com/p/what-is-killing-us-all

What (for me) an interesting, off the beaten path, topic of lab animals and do no harm, thanks.

Studying the history of medicine and the current Medical Mafia and its pHarmaceutical goons as I have for many years, I consider the Hippocratic Oath was generally never applied from Hippocrates on. I always called it the "Hypocritical Oath" since as I assume you know, Iatrogenic deaths in most Western countries rank anywhere from the third to first--competing with the illnesses of heart and cancer.

As a Voluntaryist (all governments are unnecessary evils), the medical Do No Harm is our Non-Aggression Principle; and yes, let us grow up and leave the Plantation along with the whips to be used on themselves.

Get free, stay free.